Maggie Gram is an interaction designer and—by training, before becoming a designer—a cultural historian. She leads an experience design team at Google and has taught at the Maryland Institute College of Art, Washington University in St. Louis, Ca’Foscari University of Venice, and Harvard University. Her writing has been published in n+1 and the New York Times.

What’s the big idea?

Design as an idea erupted in response to the industrialization of society. Through it, many challenges of this transition in lifestyle could be fixed or soothed. Not all design benefits quality of life—sometimes it poses new risks—but it is a powerful tool for chipping away at wicked problems and building a genuinely better world.

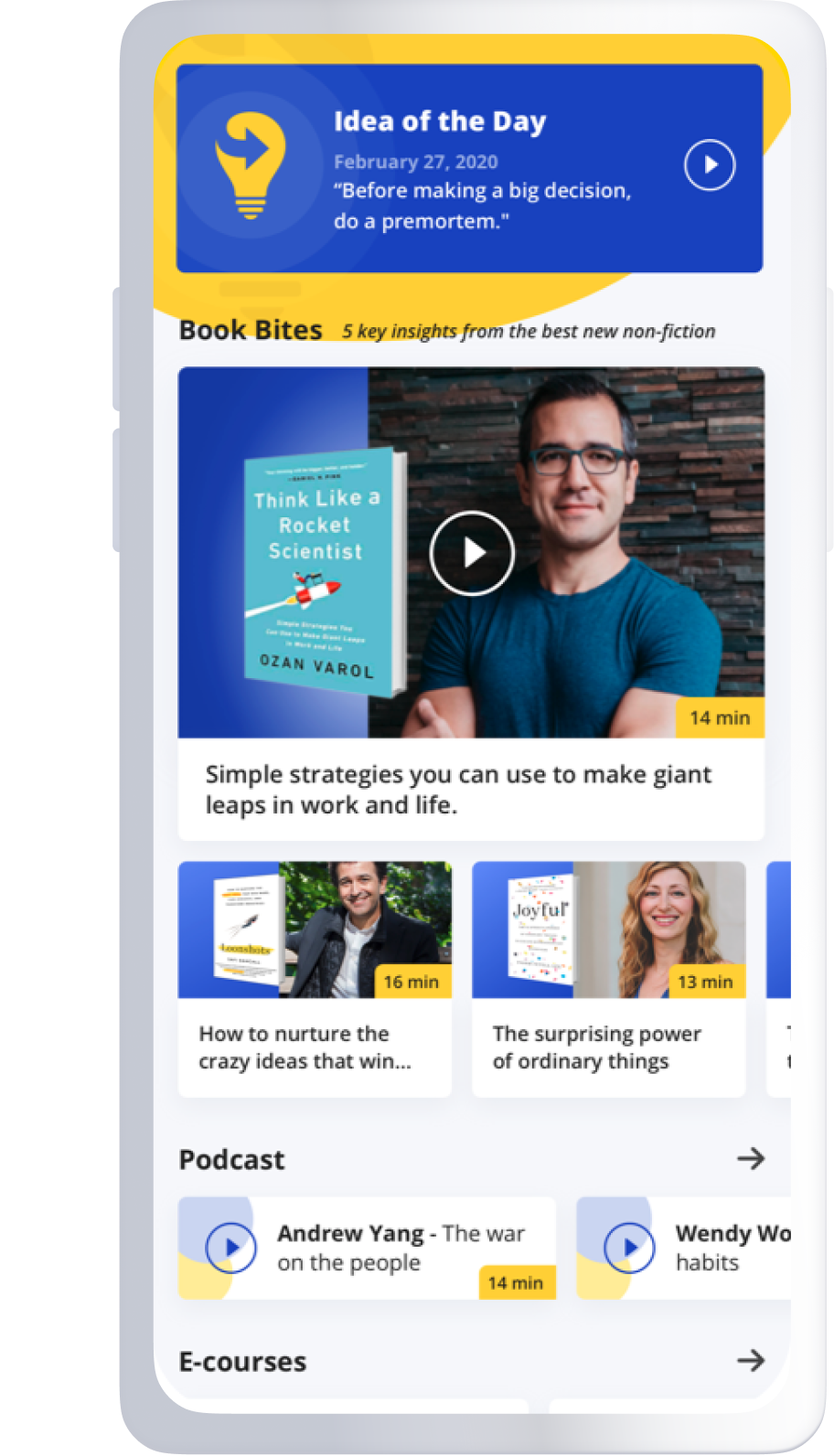

Below, Maggie shares five key insights from her new book, The Invention of Design: A Twentieth-Century History. Listen to the audio version—read by Maggie herself—below, or in the Next Big Idea App.

1. The idea of “design” can seem timeless, but it’s a pretty recent invention.

What do you think of when you hear the word “design?” Most people will probably think of something rather general and nonspecific, like when thinking of the word “art,” “power,” “love,” or “dream.” Like these ideas, the idea of “design” can seem timeless or universal. But it’s actually a pretty recent invention.

Before the 20th century, people didn’t see aesthetics, function, and problem-solving as related. Over the 20th century, they came to see all of these (as well as human-centeredness, experience, and even thinking itself) as parts of one thing: “design.” The idea of design was developed over the period from approximately 1890 to about 2010. People invented it as a concept, gradually and inadvertently, and then invested faith, hope, and capital in it.

2. There’s a reason design was invented in the 20th century.

By the 1890s, the Industrial Revolution had transformed Great Britain, most of Europe, and the United States from agrarian and handicraft economies into machine-driven industrial ones. Soon, barely regulated markets would dominate everyday life, uprooting people and polluting rivers and degrading working conditions.

“Before the 20th century, people didn’t see aesthetics, function, and problem-solving as related.”

The idea of “design,” whether it meant making things more beautiful, more human-centered, or more useful, helped make living under and participating in capitalism feel less brutal and more friendly and creative. Artists who entered industry over the course of the 20th century—Eva Zeisel, Leo Lionni, Walter Teague, Ray Eames, and countless others—became not everyday workers but “designers.” Their work was seen as not just profitable but also generative, creative, and valuable to civic life.

3. Today, the idea of design is everywhere, and we value it highly.

We read magazines like Wallpaper* (which is distributed from Montreal to New Zealand to Hong Kong) and Dwell (which not only writes about but builds prefab houses). We listen to the radio show 99% Invisible. We buy things from a Target line called “Made by Design.” When we’re feeling flush, we wander through the showrooms of “Design within Reach.” Cities from Los Angeles to Helsinki have hired Chief Design Officers. Universities pay consultants to help them implement “design thinking.” It is what we might call a design-y time.

4. Design doesn’t automatically make things better or more just.

As the critic Nikil Saval has written, “design is an inherently futurist medium.” To believe in design is to believe that human society can change for the better. This aspect is why design is particularly fetishized in Silicon Valley—that techno-utopian wonderland, with its obsessions with the new, improvement, enhancement, and optimization.

“To believe in design is to believe that human society can change for the better.”

Silicon Valley’s obsession with design has manifested in private spaceflight, Tesla cybertrucks, and a collective fixation on artificial general intelligence. But these are examples of how not all change, and indeed not all design, is inherently good. We ought to be wary of the uncritical fetishization of anything, not least design itself.

5. Despite that caution, design can be a good tool.

Just imagining and believing and “ideating,” as we say in my field of experience design, isn’t enough. Actually making things, doing things, and transforming political arrangements are necessary if we’re going to make contemporary life genuinely better and more just for more people.

The designer Sylvia Harris redesigned the U.S. Census to drive higher participation rates in Black, Latinx, and Native American neighborhoods. The U.S. Census helps determine who the U.S. government funds; the federal government relies on census data to allocate approximately $1.5 trillion across hundreds of federal programs. Redesigning the census makes a real and material difference. Design can chip away at wicked problems, and it should.

Enjoy our full library of Book Bites—read by the authors!—in the Next Big Idea App: