Greg Walton, PhD, is the co-director of the Dweck-Walton Lab and a professor of psychology at Stanford University. Dr. Walton’s research is supported by many foundations, including Character Lab, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation. He has been covered in major media outlets including The New York Times, Harvard Business Review, The Wall Street Journal, NPR, The Chronicle of Higher Education, The Washington Post, San Francisco Chronicle, and Los Angeles Times.

What’s the big idea?

Stanford psychologist Greg Walton reveals how small psychological shifts—known as wise interventions—can create profound change in our lives. Through vivid storytelling and cutting-edge research, he shows how simple reframes can build trust, strengthen relationships, and unlock potential. From a teacher’s encouraging words to a brief moment of self-reflection before conflict, these subtle shifts can shape our futures in powerful ways. Ordinary Magic is a compelling guide to harnessing everyday moments for extraordinary impact.

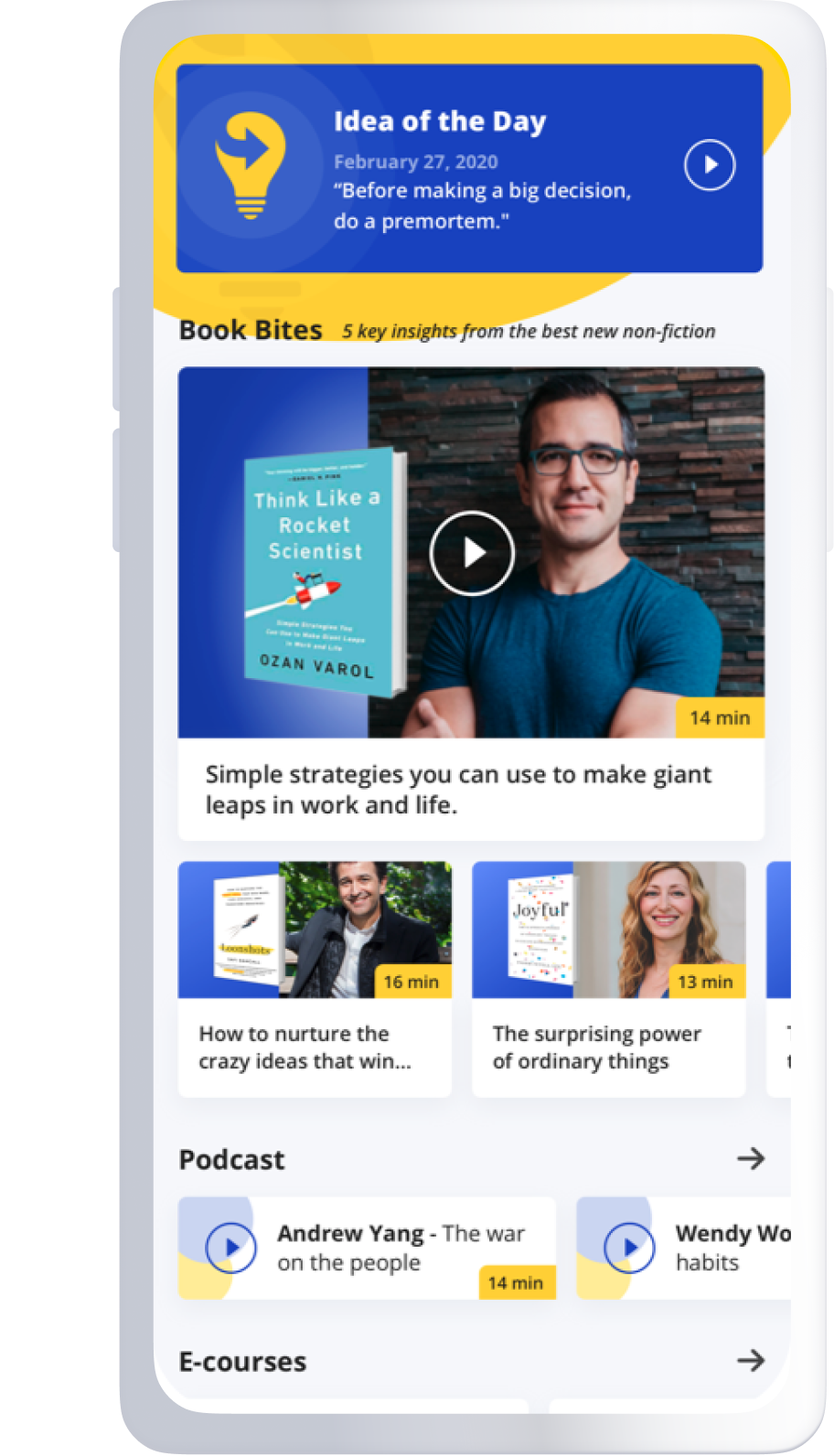

Below, Greg shares five key insights from his new book, Ordinary Magic: The Science of How We Can Achieve Big Change with Small Acts. Listen to the audio version—read by Greg himself—in the Next Big Idea App.

1. Little things can make a big difference.

Ordinary Magic is about change, and how to create it.

Sometimes, problems in our lives can seem fixed, like there’s nothing you could do to make things better. Persistent struggles in school. Conflict in a relationship. Self-doubt. But we don’t just have to wish things were better.

It starts with noticing our little thoughts and feelings—what I call surfacing—and then creating the right space to address them.

Say you’re married. It’s a happy marriage, but you and your partner have a persistent conflict. Will you have the right space to think through your conflict? One study found that seven minutes answering three reflection questions every four months for a year made conflict less distressing for couples, and helped stabilize marriages. Twenty-one minutes to save a marriage.

Or say you’re a teacher. You work hard for your students, giving them feedback so they can improve. But many of your students don’t take up that opportunity. Why? Another study found that just 17 words increased the rate at which 7th graders took up their teacher’s feedback to improve their work for a higher grade—and increased their trust in teachers over the rest of the school year.

Change like this can feel magical. But this—this is ordinary magic. These solutions require no special degree. They’re the kind of thing all of us can learn from, and put to work in our own lives. Everyone can be an ordinary magician. And all of us benefit from ordinary magicians around us.

What this magic requires is a deeper understanding of ourselves—understanding the icky questions that pop up as we travel through life. And learning how, individually and together, we can answer these questions well.

2. Big problems can start small.

A little thought, a shadow of doubt. Often, it starts with a question. But then things spiral out of control.

Suppose you wonder, “Does my partner disrespect me?”

Left to their devices, questions like this drive us down. If you think a fight means your partner doesn’t love you, then you might hold back and be less forgiving next time. If they’re late, again, you might feel confirmed in their lack of respect. Then you withdraw or lash out. That undermines a relationship.

“Left to their devices, questions like this drive us down.”

Or say you’re the first in your family to go to college. You wonder, “Do people like me belong in college?” Then you’re excluded from a social outing. A professor says something unkind. You think, “Maybe it’s true—maybe people like me don’t belong here.” You stop going to office hours, stop asking questions in class, skip that welcome event for a student group. Fast forward and, six months later, you don’t have close friends on campus. No mentor to guide your growth. You’re thinking about dropping out.

Negative questions make us spiral down. They make themselves true. Then, they put our relationships, our achievements, and our health at risk.

3. Change starts when we understand the questions we face, or another person faces.

Let me share an example: When our kids were little, we took them to and from a campus daycare by bike. So, at the end of a long day, we’d bike home, the kids on tiny 12-inch wheels. Sometimes, they’d stop two blocks from home and twenty minutes past dinner time. They’d sit on the curb and wail, “I’m tired!”

I thought of research by my good friend Veronika Job. Veronika showed that sometimes people take little cues of tiredness as a reason to stop, to pull back from their efforts, even on things they care about. It’s like we have range anxiety—you feel you’re running out when you work hard on something, long before you reach any actual limit. Then you hold back, even on something you care about.

So, I decided to reframe the meaning of feeling tired to them. I took to saying, “It’s when you’re tired and you keep going that you get stronger.”

It didn’t always work. But I think it helped.

A little later, our daughter Lucy was trying to bike up a steep and winding path on our way home. We’d taken to bringing chalk to mark how far she’d gotten. One time, Lucy not only beat her previous record but crushed it. As Oliver and I whopped and cheered, Lucy said, “You know how I did it? When I wanted to stop, I kept going.”

Isn’t that lovely?

In that story, I offered Lucy a new way to think about her efforts—that tiredness need not be a reason to stop. That she could keep going. That tiredness might even be an opportunity—to get stronger. It freed Lucy to succeed. She used that way of thinking to achieve her goal. As I write in the book, “Thinking is for becoming.”

This kind of change is quiet, not loud. But it frees us to spiral up. A small initial insight, a small change in direction, can lead us to vast new lands.

4. The icky questions we ask are reasonable, but they aren’t necessarily true.

The questions come from the context we’re in. Of course, the first-gen college student wonders if people like her belong in college. Her family literally hasn’t belonged in college before. That reasonableness is important. First, it means you’re not alone. When you’re asking a question like Do I belong?, Can I do it?, or Am I inadequate? there’s nothing wrong with you. You’re not irrational or disordered or weird. You’re normal. You’re responding to the world as it is. But even as that question is reasonable, it needn’t be true. It’s answers you’re looking for.

Because questions like these are reasonable, we can learn to predict when people will ask them. When we see these questions clearly, we can learn to address them with grace and dignity, which can transform our lives.

“That’s an hour to change a life.”

In one study, my colleagues and I developed a 60-minute session early in college to help new students address the question, “Do people like me belong in college?” Students of color are often underrepresented in college, and sometimes, they’re represented as less able and less deserving. So, that question is most pressing for them.

The exercise we developed shared stories from older students, who showed that almost everyone worries at first if they belong in college. Students reflected on their belonging worries, why they’re normal, and how they can improve with time.

That improved African American students’ achievement through the next three years of college. A decade later, they reported being more satisfied in their lives, more successful in their careers, and taking on more leadership roles in their communities. That’s an hour to change a life.

That didn’t happen because students just remembered that experience. At the end of college, students couldn’t even remember it clearly. And they didn’t credit any of their success to it. Instead, addressing a persistent question about belonging—a reasonable question that comes from the history of exclusion in education—freed students to build friendships and mentor relationships, and those supports that helped them succeed.

5. This is work we do together.

The most toxic questions are about who you are and who you can become.

In the most difficult circumstances, when people look at you and all they see is something horrible, there must be space to tell your own story, a chance to tell that story in a way that other people can hear, a way to make that story real together.

For more than a decade, I’ve worked with leaders in the Oakland Unified School District to support students returning to school from juvenile detention. This circumstance poses terrible questions to both students and teachers. These students have been told, more or less unambiguously, that they do not belong here and are not wanted here. And it’s easy for teachers to wonder, “Will this student care? Will they try? Or will they just cause trouble?”

“The most toxic questions are about who you are and who you can become.”

So, we created a platform for young people, a way for them to introduce themselves to an educator of their choice—to share their values in school, such as being a good role model for a younger sibling, their goals, and the challenges they face. We find that young people use this platform to express, essentially, “I’m a good kid, and I want to succeed, but I need help. Can you help me?” Then, we present this information to the educator the child selected. We emphasize that all kids need support from adults. This child has chosen you. Here’s what they would like you to know about them. Please help. And then we say, Thank you for your work.

We find this letter opens the hearts of educators to justice-involved youth. It helps them see that this is a kid—a kid who wants to succeed. They respond with support. In a first trial, this approach reduced the rate of student recidivism to juvenile detention by 40 percentage points, from 69 percent to 29 percent, in the following school term. It’s the most powerful way I know to remedy mistrust in school.

This is the change we need to help us achieve what we want to achieve, to do what we want to do, and to become who we want to be. It’s a way to help other people in their journeys, too. In the process, we can make our society a little healthier, a little more together, and a little kinder.

To listen to the audio version read by author Gregory Walton, download the Next Big Idea App today: